Catenae and commentaries on the Pauline Epistles: the case of the Pseudo-Oecumenian catena

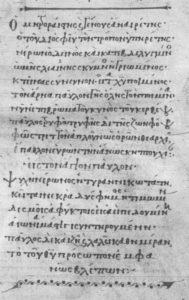

Biblical catenae are Byzantine manuscripts comprising a selection of patristic and exegetical material from multiple sources. The biblical text, usually in the middle of the page for the so-called ‘frame’ or ‘marginal’ catenae, is surrounded by the extracts from the commentaries of the early Greek Church Fathers. Alternatively, it can be followed by the exegesis in the format of a ‘full-running text’ (as for the ‘alternating’ or ‘full-page’ catenae). The oldest surviving catena on the Pauline Epistles is attributed to the seventh-century exegete Oecumenius, and is attested in eighty-five manuscripts from the tenth to the sixteenth century, limited to Romans.[1] The Pseudo-Oecumenian catena differs from the other catena traditions for the presence of anonymous, numbered extracts, which constitute the original set of comments, followed by two additional layers of scholia: the so-called Corpus Extravagantium, consisting of extracts from the Greek Church Fathers (mainly Oecumenius, Theodoret of Cyrrhus, Severian of Gabala and John Chrysostom), either preceded by the attributions or recorded anonymously, and the Scholia Photiana, which are excerpts from Photius of Constantinople’s commentary on the Pauline Epistles.[2]

The present contribution offers a first overview of the book epigrams transmitted by the Pseudo-Oecumenian manuscripts, mainly based on the DBBE records, which classify the epigrams as author-, scribe-, reader-, image-, and text-related according to their function and content in the manuscripts. However, these categories quite often overlap, as is the case of the DBBE Type 5659 illustrated below, where Chrysostom, Theodoret and Oecumenius are mentioned as both the readers of the Corpus Paulinum and the authors of their own commentaries.

With regard to their position, these epigrams are usually placed before or after the Euthalian Apparatus,[3] at the beginning of the Pauline Epistles as headings, or on the opening and closing flyleaves along with pen trials, possession notes and subscriptions. Most of them are anonymous, apart from a few epigrams attributed to Andreas Moraios (all the epigrams in London, BL, Add. 28816 [GA 203]), Theophylactos Nazeraios (Vatican City, BAV, Vat. gr. 1971 [GA 1845]), Ioannes Pepagomenos (Vatican City, BAV, Barb. Gr. 503 [GA 1952]) and Markos Mamounas (Vatican City, BAV, Pal. gr. 204 [GA 1998]).

Author-related epigrams

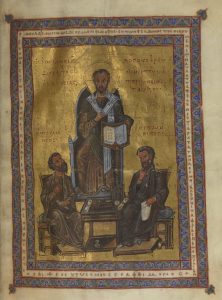

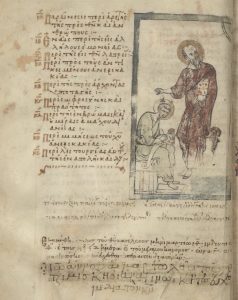

The author-related epigrams, which correspond to Lauxtermann’s ‘laudatory’ category, can praise the author of the books (Paul, e.g., DBBE Types 3166, 3170 and 3172) or early Greek Church Fathers, such as DBBE Occurrence 24099 in the manuscript Venice, BNM, Gr. Z. 34 (coll. 349) [GA 1924], which mentions Chrysostom, Theodoret and Oecumenius as commentators of the Corpus Paulinum. The same epigram is also attested in two more frame catenae of the eleventh century from Staab’s Erweiterte Typus,[4] namely Paris, BnF, Grec 224 [GA 1934] and Paris, BnF, Coislin 217 [GA 1972], with the aim to introduce the content of the book to the reader (the catena on Paul by Oecumenius). In GA 1934, the epigram is enclosed within the frame of a miniature representing the three Greek Church Fathers, which makes it an image-related epigram as well, while in GA 1972 it is copied alongside three more epigrams on Paul (Type 5188) John Chrysostom (Type 5685) and the content of the Pauline Letters (Type 6478). In Type 5659, Chrysosthom is depicted as the pivotal exegete of the Pauline Epistles, which Theodoret and Oecumenius follow as ‘interpreters’ (διηρμηνευκότες). This is further specified by Figure 2, which illustrates Chrysostom as a teacher on a throne showing the Pauline text to his disciples. In other occurrences, Chrysostom is portrayed alongside the spirit of Paul (Figure 3), who is whispering his words to the Greek Church Father (Type 7096), to legitimate his status of ‘Golden Mouth’.

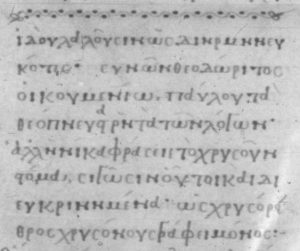

Ἰδοὺ λαλοῦσιν ὡς διηρμηνευκότες

συνὼν Θεοδώρητος Οἰκουμενίῳ

Παύλου τὰ θεόπνευστα ῥητὰ τῶν λόγων

ἀλλ’ ἡνίκα φράσειε τὸ χρυσοῦν στόμα

σιγῶσιν οὗτοι καὶ διευκρινημένα

ὡς χρυσόρειθρος χρυσόνους γράφει μόνος.

See, they speak as an interpreter – Theodoret together with Oecumenius – the God-inspired words of Paul’s writings, but as soon as the Golden Mouth speaks these are silent, and exactly explained the golden spirit writes alone like a golden stream.[5]

Ἰωάννης ἡ δόξα τῆς ἐκκλησίας

λόγους ἐρευνῶν τοὺς ἀπορρήτους Παύλου.

John, the glory of the Church, exploring the unspeakable words of Paul.

Τί ψιθυρίζεις, Παῦλε, τῷ Χρυσοστόμῳ;

οὔ σοι Θεοῦ δάκτυλος ἐγγράφει λόγους;

τὰ μυστικὰ σάλπιγγι βροντῆς ἐμπνέεις∙

παρὰ θαλασσῶν ταῦτα καὶ γῆς σαλπίσει.

What are you whispering to Chrysostomus, Paul? Doesn’t God’s finger write your words? You breathe secrets into the trumpet of thunder; he will proclaim it across seas and land.

Other laudatory epigrams focus on the power of the eloquence of Paul, adopting a language that recalls the musical imagery (Φόρμιξ, αὐλὸν τοῦ Παρακλήτου, λύραν, ὄργανόν τε τῆς Θεοῦ μουσουργίας [Type 3166]), or describing the apostle as a storm (ζάλη), a threefold wave (τρικυμία) and a hurricane (καταιγίς) (Type 6006). In another occurrence (Type 6005), Paul’s eloquence is associated with war-like images (ὄλεθρος, ὑψιμέδων, ἄλκαρ, μοναρχικός, ὁπλοφόρος), or, conversely, the Christian figures of the young lamb (ἀρήν) and the shepherd (ποιμήν) (Type 3172).[7]

Patron-related epigrams

Only two epigrams are recorded as patron-related epigrams among the eighty-five manuscripts of the Pseudo-Oecumenian catena. These include one dedicatory epigram to a βασίλισσα Μαρία, possibly Maria of Alania, wife of Michael VII Doukas, on the closing flyleaf of Athos, M. Aγ. Παύλου, 2/London, BL, Add. 19392a (σταυρὲ φύλαττε βασίλισσαν Mαρίαν: Occurrence 20260), and an invocation by an unknown monk Ματθαῖον who possessed the manuscript Jerusalem, Patriarchicke Bibliotheke, Panaghiou Taphou 38 (Κύριε, σῶσόν με τὸν δούλον Ματθαῖον μοναχὸν τὸν ἔχοντα τὴν βίβλον ταύτην: Occurrence 20559).

Scribe-related epigrams

This category of epigrams includes a variety of typologies, comprising invocations to Christ and thanksgiving for the completion of the book (Χριστέ, παράσχου τοῖς ἐμοῖς πόνοις χάριν + Τὸν ἐκ πόθου κτήσαντα τήνδε τὴν βίβλον [Occurrences 30886 + 30885], ἡ χεῖρ ἡ γράψασα σήπεται τάφω [Occurrence 24681]). Alternatively, scribe-related epigrams can also be prayers to the readers, usually introduced by the verbs εὔχεσθε or μνησθήτι, or can be associated with the colophons at the end of the manuscript and provide information about the practices of copying and writing, usually with an emphasis on the fatigue of the scribe (e.g., the ὥσπερ ξένοι Type 2148).

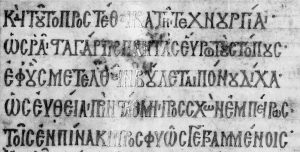

Finally, the epigram DBBE Occurrence 23121 (Type 2626) offers an indication of the scribal activity of the copyist of Paris, BnF, Grec 219 (GA 91): on ll. 8-12, the scribe admits to having appended the following tables with the metrical titles of the Acts and the Pauline Epistles to help the reader to easily find the text-passages.

καὶ τοῦτο προστέθεικα τῇ τεχνουργίᾳ.

Ὡς ῥᾷστα γάρ τις παντας εὕροι τοὺς τόπους

ἐφ᾽ οὓς μετελθεῖν βούλεται πόνου δίχα

ὡς εὐθείᾳ πρὶν στάθμῃ προσσχὼν ἐμπείρως

τοῖς ἐν πίνακι προσφυῶς γεγραμμένοις·

And I have also added this to the work of art, so that one may easily find all the passages he wishes to consult, easily and effortlessly, after he has first devoted himself to what is indicated suitably in the index, like a straight guide.

(DBBE Type 2626, Occurrence 23121, vv. 8-12)

Reader-related epigrams

Only a few epigrams among the Pseudo-Oecumenian catenae are addressed to the reader of the manuscripts, who is either asked to pray for the salvation of the patron or the scribe (Occurrences 30875: Εὔχεσθε τῷ γράψαντι Ἀνδρέᾳ ξένῳ and 30881: Μνήσθητι κἀμοῦ τοῦ ταπεινοῦ γραφέως, both preserved in London, BL, Add. 28816 [GA 203]), or to read the manuscript because of its spiritual value (Type 3167: Τὴν ἐκκάλυψιν τὴν Ἰωάννου δέχου / τοῦ φῶς ἀπαστράψαντος ὡς βροντῆς γόνου).

Text-related epigrams

Most of the epigrams that can be included within this category comprise short metrical headings before each of the Pauline Epistles (Types 4706, 5679, 5681, 4708, 4710, 4712, 4714, 4716, 4718, 4720, 4722, 4724, 4726 and 4728). However, a long metrical hypothesis on Paul (Type 3166), comprising 100 dodecasyllables preceded by the heading Ἡ τῶν ἐπιστολῶν ὑπόθεσις διὰ ἰάμβων, opens the section on the Pauline Epistles in the manuscripts GA 91, 1924, 1934 and 1972. This poem can be divided into three sections: vv. 1–21 underline the musical power of Paul (Παῦλον αὐλὸν τοῦ Παρακλήτου, Πνεύματος τοῦτον λύραν, ὄργανόν τε τῆς Θεοῦ μουσουργίας), vv. 22–66 describe the content of the letters and vv. 67–110 offer a biographical summary of Paul by mentioning contemporary figures , such as Felix, Porcius Festus, Nero, Luke and Aristarchos.

In all these manuscripts, this metrical preface is followed by two author-related epigrams establishing an opposition between Nero and the apostle (Types 3170 and 3172) , which seems to recall a similar episode in the Martyrdom of Paul within the Euthalian Apparatus.[8]

Ὁ μητροραίστης καὶ γένους ἀναιρέτης

ὁ τοῦ Διός, φεῦ, τὸν τρόπον ὑπηρέτης

Νέρων ὁ δεινὸς καὶ κατεβδελυγμένος,

ὠμῆς λεαίνης σκύμνος ἠγριωμένος

κτείνας σύνευνον, εἶτα Χριστοῦ ποιμένος

τὸν ἄρνα Παῦλον γῆς ὅλης τὸν ποιμένα,

νῦν ἐστὶ βρῶμα τοῦ κυνὸς τοῦ Κερβέρου.

Παῦλος τρυφᾷ τρυφῇ δὲ τῆς ζωηφόρου

φῶς τριττὸν ἁπλοῦν ὡς ὁρῶν θεαρχίας

ἔπαθλον εὑρὼν τὴν ἄνω σκηπτουχίαν.

The mother-murderer and annihilator of the offspring, according to his disposition, ah, servant of Zeus, Nero, the terrible and despicable, the wild cub of a rude lioness, who killed his wife, then the young lamb of Christ, the shepherd, Paul, shepherd of the whole earth, is now food of the dog Kerberos. Instead, Paul revels in the abundance of the life-giving divinity as he sees its threefold light as simple and found rulership in heaven as a battle prize.

Ψυχὴ Νέρωνος ἡ τυραννικωτάτη

κεῖται νεκρὰ δύσφημος ἠτιμωμένη

δεσμοῖς ἀφύκτοις εἰς ἀεὶ πεδουμένη

αἰωνίᾳ μάστιγι συντηρουμένη∙

Παῦλος δὲ καὶ ζῇ καὶ λαλεῖ καθημέραν

τὸ τοῦ Θεοῦ πρόσωπον ἐμφανῶς βλέπων.

The most tyrannical soul of Nero lies dead, defamed, humiliated, bound forever with ineluctable chains, kept down with an eternal whip. Paul instead is alive and speaks every day, openly seeing the God´s face.[10]

It is not a case that in GA 1924, 1934 and 1972 these epigrams are placed immediately after the set of prefaces on the Pauline Epistles comprising the Prologue (BHG 1454), the Peregrination (BHG 1457b) and the Martyrdom of Paul (BHG 1458) and the list of chapters on Romans (Von Soden 43). In addition to the same paratextual material, GA 1924, 1934 and 1972 begin the text of the Catena with a distinctive incipit (Τίνος ἕνεκεν αὐτοῦ τὸ ὄνομα…), rather than the usual Τὸ ἀποῦσι γράφειν αἴτιον τοῦ κεῖσθαι αὐτοῦ τὸ ὄνομα as the rest of the tradition, which offers further evidence in support of the relationship between these three witnesses.[11]

Conclusions and further desiderata: newly discovered epigrams

The case studies illustrated above provide a general description of the various typologies of metrical paratexts in catenae and commentaries on the Pauline Epistles, with a particular focus on the ways the figures of Paul and Chrysostom are portrayed in biblical manuscripts. The examples of DBBE types 3170 and 3172 show that paratexts, both the book epigrams and the full set of alternative paratextual material to the standard one (Prologue + Peregrination and Martyrdom of Paul + Prefaces), can be an important tool to begin investigating the relationship between biblical manuscripts (e.g., GA 1924, 1934 and 1972). In this context, the presence of the same collection of Byzantine texts absent elsewhere (explanation of the Jewish names of the Revelation, lists of patriarchs and emperors among all) can offer further evidence in support of the relationship between Paris, BnF, Coislin 224 (GA 250) and Vienna, ÖNB, Theol. gr. 302, ff. 1-353 (GA 424), which also preserve the same abbreviated version of the Pseudo-Oecumenian Catena.

Furthermore, more epigrams are yet to be discovered. The study of the paratextual material among the manuscripts of the Pseudo-Oecumenian tradition allowed me to identify some short texts which are absent from the DBBE database, even though further considerations on the metrical nature of these texts need to be done before their inclusion in the database. Among these, one scribe-related epigram is recorded by a later hand in the closing flyleaf of Vatican City, BAV, Chis. R VIII 55 (gr. 46) (GA 1951) (κύριε βοήθη [sic!] τὸ σὸ δοῦλο Θεογνόστος) and attributed to an unidentified Theognostos. This overview of book epigrams in the biblical chains was a valuable opportunity to investigate the paratextual characteristics of biblical manuscripts for the first time and to provide preliminary observations on their relevance for establishing relationships between manuscripts on a par with the main text.

Notes

[1] The Pseudo-Oecumenian catena on the Pauline Epistles is indicated by the CPG numbers C165.1–5, which refer to the five stages of the textual tradition, in the Clavis Patrum Graecorum (M. Geerard and J. Noret, eds., Clavis Patrum Graecorum: IV Concilia. Catenae [CCSG, 4] [Turnhout: Brepols, 20182]). A full list of New Testament catenae is provided in G. Parpulov, Catena Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. A Catalogue (TS 3.25) (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2021).

[2] For this terminology, see K. Staab, Die Pauluskatenen nach den handschritflichen Quellen untersucht (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1926), and K. Staab, Pauluskommentare aus der Griechischen Kirche: Aus Katenen Handschriften gesammelt und herausgegeben (Münster: Aschendorff, 1933).

[3] The Euthalian Apparatus is the set of prefatory material including the Prologue on the Pauline Epistles, the Peregrination and the Martyrdom of Paul, the Prefaces on each of the Pauline Epistles and the list of chapter titles. See further, L.C. Willard, A Critical Study of the Euthalian Appratus (ANTF 41) (Berlin, NY: De Gruyter, 2009), and V. Blomkvist, Euthalian Traditions. Text, Translation and Commentary (TU 170) (Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2012).

[4] The ultimate stage of the tradition with the additional scholia from Photius.

[5] Unless otherwise specified, all translations are by the author.

[6] Image courtesy of the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana (“su concessione del Ministero della Cultura – Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana”, 7/10/2022).

[7] A similar vocabulary related to Paul’s eloquence is also attested in the epigrams preserved in the manuscript Vat. Gr. 363 (see K. Bentein, F. Bernard, K. Demoen and M. de Groote, ‘New Testament Book Epigrams. Some New Evidence from the Eleventh Century’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 103.1 [2010], 13–23 [pp. 19–23].

[8] See further K. Demoen, R. Ricceri and M. Tomadaki, Paul in Byzantine Epigrams, in M. Cacouros and J.H. Sautel, eds., Des Cahiers à l’histoire de La Culture à Byzance : Hommage à Paul Canart, Codicologue (1927-2017) (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 306) (Leuven: Peeters, 2021), pp. 117–134 (p. 123).

[9] Image courtesy of the Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana (“su concessione del Ministero della Cultura – Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana”, 7/10/2022).

[10] Transl. in Demoen, Ricceri and Tomadaki, Paul in Byzantine Epigrams, p. 123.

[11] These manuscripts significantly are also the only witnesses to DBBE Type 5188, “Paul, the initiated into the secret words”, the verse used as the title to this blog post.

Want to read more?

- K. Bentein, F. Bernard, K. Demoen and M. de Groote, ‘New Testament Book Epigrams. Some New Evidence from the Eleventh Century’, Byzantinische Zeitschrift, 103.1 (2010), 13–23.

- F. Bernard and K. Demoen, ‘Byzantine Book Epigrams’, in W. Hörandner, A. Rhoby, and N. Zagklas, eds., A Companion to Byzantine Poetry (Brill’s Companions to the Byzantine World, 4) (Leiden, Boston: Brill, 2019), pp. 406–429.

- K. Demoen, R. Ricceri and M. Tomadaki, Paul in Byzantine Epigrams, in M. Cacouros and J.H. Sautel, eds., Des Cahiers à l’histoire de La Culture à Byzance : Hommage à Paul Canart, Codicologue (1927-2017) (Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta, 306) (Leuven: Peeters, 2021), pp. 117–134.

- H.A.G. Houghton (ed.), Commentaries, Catenae and Biblical Tradition. Papers from the Ninth Birmingham Colloquium on the Textual Criticism of the New Testament: in association with the COMPAUL project (TS 3.13) (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2016).

- M.D. Lauxtermann, Byzantine Poetry from Pisides to Geometres. Texts and Context, 1 (Wien: Verlag der österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2013), pp. 197–212.

- G. Parpulov, Catena Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament. A Catalogue (TS 3.25) (Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias Press, 2021.

- K. Staab, Die Pauluskatenen nach den handschritflichen Quellen untersucht (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute, 1926)

- K. Staab, Pauluskommentare aus der Griechischen Kirche: Aus Katenen Handschriften gesammelt und herausgegeben (Münster: Aschendorff, 1933).

- CATENA Project’s website (https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/research/itsee/projects/catena/project.aspx).

About the author

Jacopo Marcon is a doctoral candidate at ITSEE in the University of Birmingham where he is part of the ERC-funded CATENA Project. His doctoral research investigates the manuscript and textual tradition of the Pseudo-Oecumenian catena on Romans, with a particular focus on how the extracts from the patristic sources have been adapted within the context of the catena. He has previously contributed to a catalogue of the Greek manuscripts in Birmingham, and he is currently working on editing the forthcoming volume of papers from the 12th Birmingham Colloquium of New Testament Textual Criticism, alongside other colleagues from ITSEE. He was appointed as Research Assistant within the project “Die alexandrinische und antiochenische Bibelexegese in der Spätantike” at the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Jacopo Marcon is a doctoral candidate at ITSEE in the University of Birmingham where he is part of the ERC-funded CATENA Project. His doctoral research investigates the manuscript and textual tradition of the Pseudo-Oecumenian catena on Romans, with a particular focus on how the extracts from the patristic sources have been adapted within the context of the catena. He has previously contributed to a catalogue of the Greek manuscripts in Birmingham, and he is currently working on editing the forthcoming volume of papers from the 12th Birmingham Colloquium of New Testament Textual Criticism, alongside other colleagues from ITSEE. He was appointed as Research Assistant within the project “Die alexandrinische und antiochenische Bibelexegese in der Spätantike” at the Berlin-Brandenburgische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

Spread the word!

Share

Cite