The so-called Menologion (actually a Synaxarion) and the Psalterion written for, and dedicated to, Basil II (976-1025)[1] are certainly among the most famous Byzantine manuscripts handed down to us. Despite being very well-known, they cannot be dated exactly. Moreover, taking into account both the illuminations and the information provided by the introductory book epigrams (especially the Psalterion’s one, more than the Menologion’s one), we see that any attempt at dating these manuscripts could imply an interpretation of them with a specific propagandistic and ideological value. Therefore, the considerations that follow belong to the realm of hypotheses.

As I will try to prove, 979 and 992 are the only two possible dates that can be considered as termini post quos (the former for the Menologion, the latter for the Psalterion).

The following five years and events are particularly meaningful to pinpoint the time frame in which the two manuscripts were produced:

- 979: Luke the Stylite died;

- 989: an earthquake struck Constantinople and the provinces of Thracia and Bithynia;

- 992: Basil II enacted a chrysobull by which he promulgated trade concessions in favour of Venetian merchants;

- 1014: Byzantines defeated Bulgars at Kleidion;

- 1018: the triumph over the Bulgars was celebrated at Ochrida.

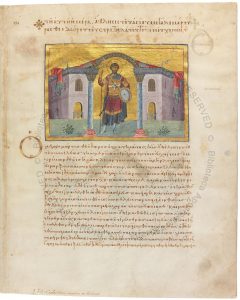

The first two dates have been generally suggested by scholars as termini post and ante quos of the Menologion: post 979 because Luke the Stylite is mentioned on December 11th, ante 989 because there is no mention of the earthquake. The last two years, instead, are implicitly considered the post quem of the Psalterion: according to a tacito consenso of most scholars, the genuflected men depicted in the famous illumination on f. IIIr are identified as defeated Bulgars (image 1).[2]

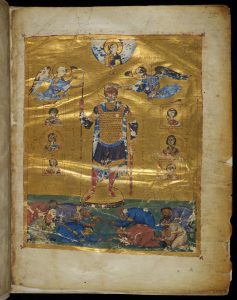

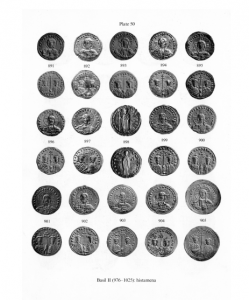

Anthony Cutler, however, proposed to date the Psalterion between 1001 and 1005, according to a numismatic analogy: the diadem of the crown, which Christ is laying upon the sovereign’s head in the illumination resembles the one on the observe of a histamenon (i.e. a golden solidus) minted during that four-year period (image 2).[3]

Although there is a certain resemblance between the two crowns, it seems to me hasty to propose such a specific dating. Each coin is a stand-alone product as a handmade artifact, influenced by the individual peculiarity of each mint. Moreover, we should not rule out the possibility that histamena representing different types of diadems may have been lost or irreversibly damaged by the passing of time. For these reasons, there is great uncertainty in defining the shape and the exact type of these coins during their circulation period. Moreover, if we consider other histamena coined during Basil II’s kingdom, we notice that there are no major differences in crown’s representations among different coins.

Antonio Iacobini has pointed out another detail that allows to examine the question of the dating of the two manuscripts more in depth and to hypothesize that the Psalterion might have been written and illuminated later than the Menologion, probably after 992. Iacobini has highlighted that both the clothes and the face of Basil II on the Psalterion’s illumination (image 1) closely resemble the representation of Saint Theodore of Amasea at p. 383 of the Menologion, related to February 8th (image 3).[4] These two miniatures were both produced by the icon painter Pantoleon.[5]

It is meaningful that the emperor is portrayed like the saint himself: Saint Theodore of Amasea was the first patron saint of Venice, and his church used to stand in the very same place where Saint Mark’s Basilica is currently standing (image 4).[6] I argue that through his representation in the miniature of the Psalterion, Basil made a political “marketing stand”, a kind of reverential homage towards an ally. As it is well known, Basil II, with the chrysobull issued in 992, established a strong economical-military relationship with Venice, and under his successors there were productive diplomatic exchanges between the two powers.

As said above, the genuflected men on the illumination (image 1) are usually identified with the defeated Bulgars, but the Marciana illumination is a rather typical imperial representation and totally complies with the Eastern figurative tradition, in which characters are deliberately depicted in different sizes based on their importance. For this reason I tend to consider more plausible Cutler’s theory, according to which the genuflected men are not the Bulgars, but a stereotypical representation of the Anatolian Byzantine aristocracy, fought by the emperor during his rise to power. Therefore, the ἐχθροί, quoted at v. 11 of the ekphrastic book epigram at f. IIv of the Psalterion, should be intended not as hostes but as inimici, i.e. domestic adversaries of the Byzantine state whom the emperor confronted during his first decade of reign (specifically, the protectorate of Basil Lekapenos the “Parakoimomenos” and to the civil war lead by Bardas Skleros and Bardas Phokas).[7]

According to the above-mentioned perspective, I draw the conclusion that the Psalterion was composed twenty-two to twenty-six years prior to the previously hypothesized date (i.e. 1014 and 1018). In light of the elements discussed above, we can cautiously conclude that the Menologion was most probably written after 979 and the Psalterion after 992.

Notes

[1] The Menologion: Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. gr. 1613 (Diktyon 68244). The Psalterion: Venezia, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Marc. Gr. Z 17 coll. 421 (Diktyon 69488).

[2] In this way, the Venice codex was dated to 1020 by H. Hunger, Schreiben und lesen in Byzanz: die byzantinische Buchkultur (Munich 1989), p. 44 and by S. Kotzabassi, Codicology and Palaeography, in V. Tsamakda (ed.), A Companion to Byzantine Illustrated Manuscripts (Boston 2017), p. 32-52: 50.

[3] Cutler exposed his theory in his paper The Psalter of Basil II, id. Imagery and Ideology in Byzantine Art (London 1992), nr. III at p. 23-25, at p. 24: « […] on this histamenon the crowns of both emperors carry bifild pendila […] these rows of pearls divide at the lowest point beside the jaws of Basil and his brother Constantine», a distinction which «is equally visible in the manuscript portrait». For the relevant coins, see the catalogues edited by P. Grieson, Byzantine Coins (Los Angeles 1982), p. 198-199 and Plate 50 (especially, nr. 904) and Catalogue of the Byzantine Coins in the Dumbarton Oaks Collection and in the Witthermore Collection, vol. III.2 (Washington D.C. 19932), p. 607 and Plate 44 (nr. 4a-4d).

[4] A. Iacobini, Il segno del possesso: committenti, destinatari, donatori nei manoscritti bizantini dell’età macedone, in F. Conca – G. Fiaccadori (eds.), Bisanzio nell’età dei Macedoni: forme della produzione letteraria e artistica. VIII Giornata di Studi Bizantini (Milano, 15-16 marzo 2005) (Milano 2007), p. 151-194: 178.

[5] On Pantoleon and the other painters of the Menologion, see A. Zakharova, Los ocho artistas del «Menologio de Basilio II», in F. D’Aiuto (ed.), El «Menologio de Basilio II», Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. gr. 1613. Libro de estudios con ocasión de la edición facsímil (Madrid – Atene – Città del Vaticano 2008), p. 131-195.

[6] Theodore’s memory in Venice is still preserved: if we look at the two columns of Saint Mark Square, overlooking the homonymous Bacino, between Duke’s Palace (on the left) and the Marciana Library (on the right), the right column is topped by Saint Theodore of Amasea («San Tòdaro», in Venetian dialect) who is about to kill a dragon. Viewers may confuse him with Saint George by analogy, because of the homonymous islet on the other side of the Bacino. On the two columns, see G. Tigler, Intorno alle colonne di Piazza San Marco, «AttiVen» 158.1 (1999-2000), p. 1-46; on the ancient church of Theodore, see F. Corner, Notizie storiche delle chiese e monasteri di Venezia e di Torcello tratte dalle chiese veneziane e torcellane (Padua 1758), p. 229-230.

[7] On Basil Lekapenos and the role of imperial servants, see C. M. Mazzucchi, Dagli anni di Basilio parakimomenos (cod. Ambr. B 119 sup.), «Aevum» 52.2 (1978), p. 267-316: 267-276; on Bardas Skleros and Bardas Phokas, see C. Holmes, Basil II and the Governance of Empire (Oxford 2005), p. 240-298.

Want to read more?

- D. Bianconi, Libri e letture di corte a Bisanzio da Costantino il Grande all’ascesa di Alessio I Comneno, in Le corti nell’alto medioevo. Atti della Settimana di Studio (Spoleto, 24-29 aprile 2014) (Spoleto 2015), p. 767-816.

- F. D’Aiuto (ed.), El ‘Menologio de Basilio II’, Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. gr. 1613. Libro de estudios con ocasión de la edición facsímil, Edición española a cargo de I. Pérez Martín (Città del Vaticano – Atenas – Madrid 2008).

- P. Degni, Nuovi codici del copista del cosiddettoMenologio di Basilio II, «MEG» 18 (2018), p. 111-126

- S. Der Nersessian, Remarks on the Date of the Menologium and the Psalter Written for Basil II, «Byzantion» 15 (1940-1941), p. 104-125.

- A. Rhoby (ed.), Ausgewählte byzantinische Epigramme in illuminierte Handschriften (Vienna 2018).

- L. Ricciardi, «Un altro cielo»: l’imperatore Basilio II e le arti, «RivIstArch» 61 (2011), p. 103-145.

- I. Ševčenko, Ideology, Letters and Culture in the Byzantine World (London 1982), nr. XI and XII.

About the author

Alberto Longhi (Venezia, 1992) obtained an MA in Classics at the University of Milan and a diploma in Greek Paleography at the Vatican School of Paleography. He is a teacher in Italian high schools and dedicates himself to research in philological and literary contexts as an independent researcher. His research interests focus on 11th-century Byzantine literature and the transmission of the Greek classics in humanistic Florence (especially on Poliziano).

Alberto Longhi (Venezia, 1992) obtained an MA in Classics at the University of Milan and a diploma in Greek Paleography at the Vatican School of Paleography. He is a teacher in Italian high schools and dedicates himself to research in philological and literary contexts as an independent researcher. His research interests focus on 11th-century Byzantine literature and the transmission of the Greek classics in humanistic Florence (especially on Poliziano).

In addition to research and teaching, he has also devoted time to writing poetry, which he self-published in some collections.

Spread the word!

Share

Cite