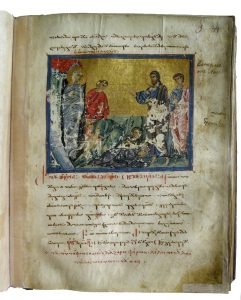

While waging war against the Georgians in 1021-1022, Emperor Basil II employed as his envoy one of their bishops, who consequently ended up in far-away Constantinople and could not return home before 1030. The prelate, named Zachariah, was a wealthy man and had several books and religious objects made in the Byzantine capital at his expense. Perhaps the last of these commissions survives, in part, as codex A 648 at the Georgian National Centre of Manuscripts. The volume must have once comprised at least three hundred and four parchment leaves (one of its quires was numbered 38 / ლჱ)[1] but now retains just seventy-two of them. Luckily these preserve a note from the book’s Georgian scribe who records his name (Basil),[2] the names of the reigning emperor (Romanus) and of the current patriarch (Alexis), the place where he worked (‘great city of Constantinople New Rome’), and a year corresponding to AD 1030. This matter-of-fact entry is followed by a high-flown Greek poem (DBBE Occurrence 17023) urging any reader who beholds ‘the commemorations and feasts for the whole year inscribed in the present book day by day [to] admire the skill of the painter’.[3] Unlike Basil, this nameless painter was evidently not Georgian, because most of the seventy-six miniatures now extant in the manuscript carry Greek captions.[4]

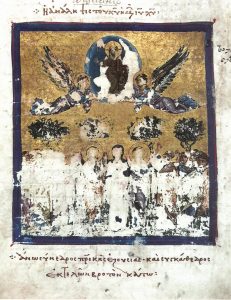

Every image marks the beginning of а chapter that briefly recounts the life of a saint or the significance of an event from Christ’s life. These texts, which Dali Chitunashvili recently published in print, are arranged according to the church calendar, starting with 1 September, feast day of St Simeon and of St Mamas.[5] The miniatures themselves were thoroughly studied half a century ago by Gaiane Alibegashvili. Their accompanying captions are of two kinds. Some, in plain prose, simply identify the person or scene depicted, e.g. ‘His All-Holiness Patriarch Alexis raising the cross’ (Ὑψῶν τὸν σταυρὸν Ἀλέξιος ὁ ἁγιώτατος πατριάρχης) on f. 5v or ‘The birth of our Lord Jesus Christ’ (Ἡ γέννησις τοῦ Κυρίου ἡμῶν Ἰησοῦ Χριστοῦ) on f. 22r. Others, in twelve-syllable verse, make brief religious statements. I reproduce this latter series on the basis of Dr Chitunashvili’s editio princeps[6] but with some corrections derived from photos of the actual manuscript. The punctuation and spelling are those of the original.[7] I have resolved all abbreviations and normalised the accents. The English translations are mine.

- (f. 4r) Birth of the Virgin

Ἰωακεὶμ Ἄννης τε Μῆτερ Παρθένε· τεχθεῖσα τέξεις τὸν πρὸ αἰώνων λόγον.

Born of Joachim and Anna, you, Virgin Mother, will give birth, to the pre-eternal Word. - (f. 5v) Elevation of the Cross

Σταυροῦ τὸ πανσέβαστον εὑρέθη ξύλον· καὶ διαμόνων κάκιστος ἐπτώθη πλάνη.

The Cross’s venerable wood once found, the demons’ evil falsehood was cast down.

(This is a reference to the legalisation of Christianity by Emperor Constantine, whose mother Helena discovered the relic of the True Cross. ‘The demons’ evil falsehood’ is the religion of the pagans.) - (f. 22r) Nativity

Ὦ γαστέρος χώρημα σεπτὸν ἀγγέλοις· ἐκ σοῦ Θεὸς προῆλθεν ἀσπόρω τόκω.

O womb which angels worship, from you God was born without a seed and came forth. - (f. 26r) Baptism

Σοῦ Χριστὲ βαπτισθέντα εὗρεν ἡ φύσις· κάθαρσιν ὄντως ψυχικῶν μολυσμάτων.

When you, O Christ, were baptised, nature found a true means for the cleansing of sin’s filth. - (f. 34r) Raising of Lazarus

Τὰ τοῦ τάφου σημεία Λάζαρος φέρων· λέλοιπεν ἅδην τῶ λόγω σου Παντάναξ.

Carrying the marks of the tomb, Lazarus has through your word, King of All, escaped from the underworld.

- (f. 35v) Palm Sunday

Χριστοῦ μολοῦντος πρὸς πάθος ζωηφόρον· ὠσάννα κραυγάζουσιν πέδες σὺν κλάδοις.[8]

‘Hosanna’, shout branch-bearing children; Christ goes to his life-bearing Passion. - (f. 36r) Betrayal

Πωλῆ μαθητὴς τὸν διδάσκαλον λόγω·[9] πλέκη δὲ τὸν κάκιστον ἀγχώνης βρόχον.

A disciple sells his master with a word, thus plaiting strangulation’s evil noose.

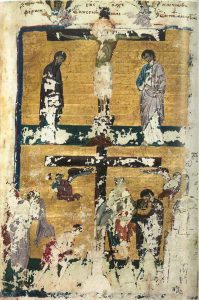

(The latter refers to Judas’ suicide.) - (f. 39r) Crucifixion

Σταυροπαγὴς ὁ Χριστὸς καὶ πάθη φέρων· ἔλυσεν ἡμᾶς ἐκ παθῶν ἁμαρτίας.

Fixed to the cross and suffering, Jesus Christ released us from the sufferings of sin.

Deposition

Φρικτὸν καθεῖλεν Χριστὸν Ἰωσὴφ ⟨τοῦ⟩ ξύλου· σὺν Νικοδήμω καὶ δίδωσι τῶ τάφω.[10]

Together with Nicodemus, Joseph has taken Christ’s formidable [body] down from the wood and is placing it in the tomb.

- (f. 40r) Resurrection

Ἅδην πατήσας Χριστὸς ἠγέρθη τάφου· καὶ τὴν πεσοῦσαν ἐξανέστησε φύσιν.

Christ, trampling on the underworld, left the tomb and raised up all of nature from its fall.

(DBBE Occurrence 30529) - (f. 45v) Christ and the Samaritan woman

Ὕδωρ δέδεκται καὶ γυνὴ[11] ζωηφόρον· ξηραίνων αὐτῆς τὴν χύσιν τῶν πταισμάτων.

A woman has received life-bearing water that dries up the spilled liquid of her sins. - (f. 46v) Healing of the blind man

Ἔβλεψε τυφλὸς ἐκ τόκου βεβυσμένος· Χριστὸς γὰρ ἦλθεν ἡ πανόματος χάρις.

One who was blind from birth began to see, since Christ came, who is grace to all our eyes.

- (f. 48v) Ascension

Ἄνω σύνεδρος πατρικῆς ἐξουσίας· καὶ συγκάθεδρος ἐκτελῶν βροτὸν κάτω.

Enthroned in power with [His] Father above, He also sat with mortals down below. - (f. 59v) Sts Peter and Paul

Χριστοῦ μαθηταὶ Πέτρε καὶ Παῦλε πρώμοι· φρουρεῖτε πάντας ὡς μιμιταὶ τοῦ πάθους.

Watch over all [of us], Peter and Paul, foremost disciples of Christ, who imitated His death.

(Like Jesus Christ himself, the apostles Peter and Paul were executed.) - (f. 65v) Beheading of St John the Baptist

Τὸν παμφαεί σου λύχνον Ἡρώδις σβέσας· βαπτιστὰ Χριστοῦ παντὸς ἐπλήσθη ζώφου.

Extinguishing your brightly shining light, Herod was filled with all manner of darkness, O Christ’s Baptist. - (f. 70r) Healing of the crippled woman

Χριστὸς ἰάται τὴν συγκύπτουσαν λόγω.

With [his] word Christ heals the woman [who was] bent over. (Luke 13:11)

It must be remembered that these verses were once read not from a computer screen but from the pages of the manuscript itself, in conjunction with the painted images they accompany. They strikingly differ from the gallery labels which museum-goers nowadays read or (more often) ignore. The Virgin [1, 3], Christ [4, 5], Peter and Paul [13], and John the Baptist [14] are addressed directly, in the second person singular, just as a worshipper would address God or one of His saints in prayer. Present-tense or future-tense verbs transport one back to the moment when something actually occurred: Mary, just born, will bear (τέξεις) the Son of God [1], the children of Jerusalem are shouting (κραυγάζουσιν) ‘Hosanna’ [6], Joseph is now depositing (δίδωσι) Christ’s dead body into the tomb [8], and so on. The use of a first-person pronoun places all readers/viewers, as it were, inside the story: crucified long before our time, Christ saved us (ἔλυσεν ἡμᾶς) by His death [8]. Enlivened by the poems, the images turn from mute memorials to a sacred past into tokens of a reality eternally present and personally experienced through faith.

Notes

[1] Assuming that the quires (gatherings) were all quaternia of eight leaves each, 38 × 8 = 304.

[2] For specimens of his handwriting see Z. Aleksidze, B. Kudava et al., Dated Georgian Manuscripts 9th-16th cc.: An Album (Tbilisi 2015) 71-72.

[3] Full English translation in I. Ševčenko, ‘The illuminators of the Menologium of Basil II’, Dumbarton Oaks Papers 16 (1962) 245–276 at 274. The Greek text in DBBE is normalised; the manuscript actually reads Βίβλω γραφῆσας τῆδε τὰς καθ᾽ ἡμέραν etc. The poem is written in ‘epigraphic’ majuscule. In its present state it ends somewhat abruptly and may have continued on a facing page, now lost.

[4] Some of the pictures proper have been cut out of the leaf, so that only their captions remain.

[5] The movable (Paschal) feast cycle is inserted after 25 March, feast day of the Annunciation.

[6] მცირე სვნაქსარი, 84-87.

[7] The scribe marks the end of each verse with a high point. He never writes the mute iotas. His spelling is far from perfect: epigram [7], for example, has πωλῆ for πωλεῖ, πλέκη for πλέκει, and ἀγχώνης for ἀγχόνης; epigram [11] has πανόματος for πανόμματος; epigram [12] has βροτὸν for βροτῶν; epigram [14] has παμφαεί for παμφαή, etc.

[8] This epigram is written in a wobbly hand that does not occur elsewhere in the manuscript. Its scribal accentuation is positively bizarre: Χ(ριστο)ῦ μολοῦντος προς πάθος ζῶὴφόρον· ὦσἂννα κραῦγάζοὺσὶν πέδες σὺν κλάδοις.

[9] Τὸν διδάσκαλον Λόγον (referring to Christ as the Word of God) would make better sense, since Judas betrayed Jesus with a kiss, not with a word.

[10] Metri gratia, I have added the word τοῦ, which the scribe may have inadvertently omitted.

[11] The word κ(αὶ) is abbreviated in the manuscript; ἡ γυνὴ would make better sense.

Want to read more?

- ექვთიმე მთაწმიდელი, მცირე სვნაქსარი, ed. D. Chitunashvili (Tbilisi 2021)

- G. Alibegashvili, Художественный принцип иллюстрирования грузинской рукописной книги XI-начала XIII веков (Tbilisi 1973) 12-74 with plates 1-35

- N. Kavtaria, K. Tatishvili, and E. Dughashvili, The Biblical Scenes in the Decoration of the Georgian Manuscripts (Tbilisi 2016) (source of the illustrations, see pp. 54, 66, 73, 79)

- for more book epigrams in illuminated manuscripts, see A. Rhoby, Ausgewählte Byzantinische Epigramme in Illuminierten Handschriften (Vienna 2018)

About the author

Georgi Parpulov (M.A. History, Ph.D. History of Art) studies manuscripts, icons, and the like. He recently published Magnificent Icons in Bulgaria (2021), Catena Manuscripts of the Greek New Testament (2021), and Middle-Byzantine Evangelist Portraits (2022).

“I sincerely thank Zaza Skhirtladze and Dali Chitunashvili for helping me to write this blog post.”

Spread the word!

Share

Cite