Epigrams often include descriptive details about the images and things that they adorn. For example, the epigram in a menologion (Oxford, Bodleian Library, gr. th. f. 1) describes the pearls, silver, and gold that decorated the book’s cover; an epigram in a lectionary (Mount Athos, Mone Megistes Lauras Α 103 [Eustratiades 103]) describes an accompanying miniature of a monk in an act of petition; and an epigram painted on a cross in another menologion (Mount Sinai, Mone tes Hagias Aikaterines, gr. 500) describes itself as the adornment for the book. These epigrams are certainly descriptive, but can we properly call them ekphraseis?

Ekphrasis is the rhetorical art of describing, but it is very different from straightforward description. While the latter is meant to convey the outward details of the subject, the former “opens up” those details with the quality of enargeia, or vividness; dialog, emotion, and sensory evocations help move the audience to clearly visualize the subject in their imagination.[1] As a literary work that could be read, performed, and heard, ekphrasis functions — according to one late antique writer — to “make hearers into spectators” (ἣ δὲ πειρᾶται θεατὰς τοὺς ἀκούοντας ἐργάζεσθαι).[2] In this way, an ekphrasis on a work of art might focus the audience’s vision in two directions: to the physical thing and to the image painted in the mind.[3] The purpose of activating these two modes of vision is explained by Nicholas Mesarites in his ekphrasis of the Church of the Holy Apostles in Constantinople, likely performed on 29 June 1200:

οἶδε γὰρ καὶ νοῦς προκόπτειν ἐκ τῶν κατ’ αἴσθησιν κἀκ τοῦ ἐλάττονος ποδηγούμενος καταλαμβάνειν τὰ τελεώτερα καὶ πρὸς τὰ ἄδυτα παρεισδύνειν, ἐφ’ ἅπερ τὸ ποδηγῆσαν αὐτὸν οὐδ’ ὁπωσοῦν παρακύψαι δεδύνηται. (…) εἰ γὰρ μὴ κύριος δι’ ὑμῶν οἰκοδομήσει μοι οἶκον τοῦτον, ὃν ταῖς ἐκ λόγου ὕλαις καὶ τοῖς ἐκ νοὸς τεχνουργήμασιν οἰκοδομῆσαι προὐθέμην, ἵν’ ἔχοιμι δι’ αὐτοῦ κἀγὼ καὶ πᾶς φιλαπόστολος πρὸς τὸ τοῦ ὑμετέρου οἴκου κάλλος τρανότερόν τε καὶ καθαρώτερον ἐνορᾶν, εἰς μάτην οἱ οἰκοδομοῦντες ἀνθρώπινοί μοι λογισμοὶ καὶ λόγοι κεκοπιάκασι.

Guided by the inferior [faculty of sight] the mind is capable on the basis of sense data of grasping essential [truths] and of penetrating to the [threshold of the] innermost mysteries, but it is incapable of even glimpsing these, if the [faculty of sight alone] serves as a guide. (…) It is my purpose to build this house [of the Lord] with words as materials and with the mind as architect, so that I and all devotees of the apostles [will have a chance] to see the beauty of your house more distinctly and more clearly, but devoting my mental faculties, which are only human, to the task of construction will have been to no purpose should the Lord [not direct you] to erect the house on my behalf.[4]

Ekphraseis thus help the audience perceive truths that were otherwise imperceivable by the physical sense of sight alone. Creating images and impacting the audience to this degree requires a great many words, a luxury that most epigrams – due to the space limitations of their written surface areas – tend not to have. As Marc Lauxtermann observes, epigrams inscribed on works of art are too short to elaborate on the “emotional depth and narrative width” that is required to develop ekphrastic themes.[5] Manuscripts have more space. Book epigrams thus have the potential to flesh out the imagery and to possess the enargeia required for ekphraseis to work. However, most book epigrams that are directed to paintings in a manuscript tend to be limited to just a few verses and rarely exceed one side of a folio. See, for example, the blog post by Georgi Parpulov.

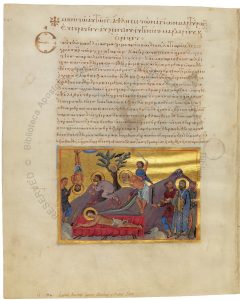

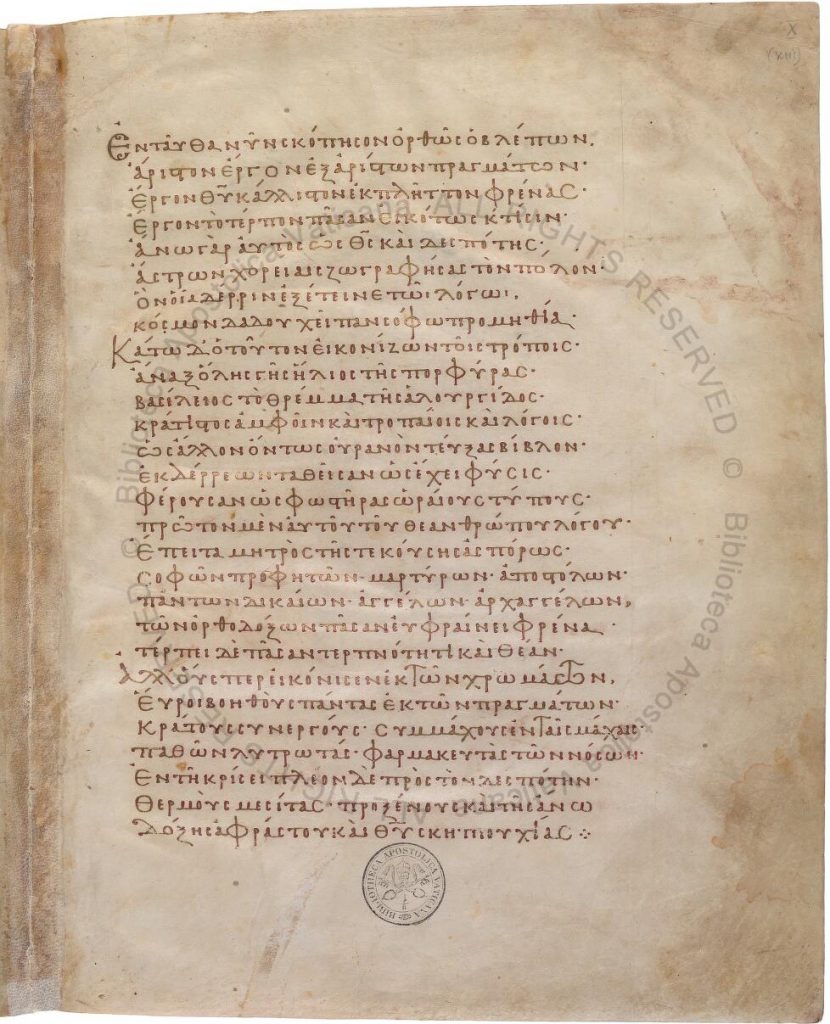

While epigrams cannot be ekphraseis in the technical sense, they may possess features that allow them to do the work of ekphraseis, albeit in an abridged format. Let’s take a look at the Menologion of the Emperor Basil II (Vatican City, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. gr. 1613), a sumptuous manuscript, made sometime after 979 and filled with images and short readings on the lives of saints (image 1). An epigram, placed on the very first page of the manuscript, introduces this luxurious work to us (image 2):

ἄριστον ἔργον ἐξ ἀρίστων πραγμάτων,

ἔργον Θεοῦ κάλλιστον ἐκπλῆττον φρένας

ἔργον τὸ τέρπον πᾶσαν εἰκότως κτίσιν.

(5) ἄνω γὰρ αὐτὸς ὡς Θεὸς καὶ Δεσπότης

ἄστρων χορείαις ζωγραφήσας τὸν πόλον,

ὃν οἷα δέρριν ἐξέτεινε τῷ λόγῳ

κόσμον δᾳδουχεῖ πανσόφῳ προμηθίᾳ·

(10) ἄναξ ὅλης γῆς, ἥλιος τῆς πορφύρας,

Βασίλειος, τὸ θρέμμα τῆς ἁλουργίδος,

κράτιστος ἀμφοῖν, καὶ τροπαίοις καὶ λόγοις,

ὡς ἄλλον ὄντως οὐρανὸν τεύξας βίβλον

ἐκ δέρρεων ταθεῖσαν, ὡς ἔχει φύσις,

(15) φέρουσαν ὡς φωστῆρας ὡραίους τύπους

πρῶτον μὲν αὐτοῦ τοῦ θεανθρώπου Λόγου,

ἔπειτα μητρὸς τῆς τεκούσης ἀσπόρως,

σοφῶν προφητῶν, μαρτύρων, ἀποστόλων,

πάντων δικαίων, ἀγγέλων, ἀρχαγγέλων·

(20) τῶν ὀρθοδόξων πᾶσαν εὐφραίνει φρένα,

τέρπει δὲ πᾶσαν τερπνότητι καὶ θέαν.

εὕροι βοηθοὺς πάντας ἐκ τῶν πραγμάτων,

κράτους συνεργούς, συμμάχους ἐν ταῖς μάχαις,

(25) παθῶν λυτρωτάς, φαρμακευτὰς τῶν νόσων,

ἐν τῇ κρίσει πλέον δὲ πρὸς τὸν Δεσπότην

θερμοὺς μεσίτας, προξένους καὶ τῆς ἄνω

δόξης ἀφράστου καὶ Θεοῦ σκηπτουχίας.

[Verses 1–8] Here now, rightly contemplate, O Beholder, the best work, made of the best deeds, a most beautiful work of God, astounding to the mind, a work that rightly delights all Creation. For above, Himself as God and Lord, having painted, with a circling dance of stars, the heavens — which by his word he stretched out like leather — to illuminate the world by his all-wise forethought.

[Verses 9–21] And below, the one who imitates him by his manner, the ruler of the whole earth, Basil, sun of the purple, the offspring of the purple robes, exceedingly mighty in both victories and words, made this book, truly like another heaven, stretched out from leather, as is natural, bearing beautiful pictures like stars: first that of the God-man Logos himself, then that of his mother who gave birth without seed, of wise prophets, martyrs, apostles, of all righteous, angels, archangels. He gladdens the minds of all the orthodox, and delights in the loveliness of every spectacle.

[Verses 22–28] But for all those he had depicted in colors, may he find all the active helpers, collaborators in his dominion, allies in battles, redeemers from afflictions, healers of sicknesses, but — more so in the judgment before the Lord — passionate mediators and providers of unspeakable glory above and the dominion of God.[6]

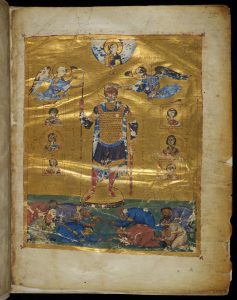

The descriptive elements suggest that this epigram accompanied an image of God and the Emperor Basil II, but no such depiction exists in the manuscript. Scholars have suggested the scene could have resembled the frontispiece in a Psalter also made for Basil (Venice, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana, Gr. Z. 17 [=421]) (image 3). In the Menologion, the verso of this folio and the recto of the next are blank, leaving no traces of a preexisting image.[7] This absence allows us to consider the autonomy of the epigram, and how its ekphrastic features help the reader visualize an image in the mind.

A direct address to the beholder in the first verse is one of these features. A rhetorical topos for many epigrams on works of art, including many book epigrams, such an invocation also had the power to draw the beholder’s attention to the object and to the images conjured in the imagination. It was also a device well attested in Byzantine ekphraseis on works of art. In his ekphrasis on the Christological cycle of mosaics in the Holy Apostles, Mesarites makes repeated invocations to his audience, involving them through imagined dialog and actions. In this way, the audience relives the scenes as they unfold in present time, becoming active participants in, and beholders of, the biblical events. Such active listening, looking, and imagining is also suggested by the Menologion epigram. In the first verse, the beholder is asked to see and contemplate the work in front of them, whether it was a now lost image or the codex as a whole. Either way, this invocation triggers a series of scenes that begin with God’s creation of the heavens and continue with Basil’s making of the manuscript. Straight away, we are invited to behold and take part in the imagery that unfolds before us.

The top-down sequence in which the epigram describes this imagery also suggests a relationship to ekphrasis. According to the instructions given in the Progymnasmata, the textbooks used for teaching rhetoric in Byzantium, this sequence was the ideal structure for ekphraseis of people.[8] The top-down structure instilled order and helped the audience easily perceive the image as it was slowly painted in the mind. But this structure was not simply an organizational method. It also communicated the loci of power within the image. By ordering the description of God in the heavens above and Basil on earth below, the poet was able to convey the ways in which the latter “imitates” the former. Basil is the sun around which the “stars” of saints coalesce in support. Even without a painted image to aid the reader, the top-down organization of the epigram and the cosmological imagery allowed the beholder to visualize the diagrammatic structure of the scene, and comprehend its ideological meaning.

The epigram’s emphasis on the materiality and making of the manuscript is another feature borrowed from ekphraseis. In Homer’s description of the shield of Achilles, the prototypical ekphrasis of ancient literature, the author begins with Hephaestus firing up the bellows and working the different parts of metal. Before we even read about iconographic compositions depicted on the shield, we experience the maker’s physical manipulation and wielding of the raw materials.[9] Likewise, when Paul the Silentiary, in his sixth-century ekphrasis of Hagia Sophia, turns his focus to the marbles, he builds his church with words by describing the masons quarrying stones and fitting them into place:

(…) τόδε γὰρ τεχνήμονι κόσμωι

(615) ἠνύσθη περὶ σεμνὸν ἀνάκτορον, ὄφρα φανείη

φέγγεσιν εὐγλήνοισι περίρρυτον ἠριγενείης.

Καὶ τίς ἐριγδούποισι χανὼν στομάτεσσιν Ὁμήρου

μαρμαρέους λειμῶνας ἀολλισθέντας ἀείσει

ἠλιβάτου νηοῖο κραταιπαγέας περὶ τοίχους

(620) καὶ πέδον εὐρυθέμειλον; ἐπεὶ καὶ χλωρὰ Καρύστου

νῶτα μεταλλευτῆρι χάλυψ ἐχάραξεν ὀδόντι

καὶ Φρύγα δαιδαλέοιο διέθρισεν αὐχένα πέτρου,

τὸν μὲν ἰδεῖν ῥοδόεντα, μεμιγμένον ἠέρι λευκῶι,

τὸν δ’ ἅμα πορφυρέοισι καὶ ἀργυφέοισιν ἀώτοις

(625) ἁβρὸν ἀπαστράπτοντα.

These [marbles] have been fashioned with cunning skill about the holy building that it may appear bathed all round by the bright light of day. Yet who, even in the thundering strains of Homer, shall sing the marble meadows gathered upon the mighty walls and spreading pavement of the lofty church? Mining [tools of] toothed steel have cut these from the green flanks of Carystus and have cleft the speckled Phrygian stone, sometimes rosy mixed with white, sometimes gleaming with purple and silver flowers.[10]

The working of materials is also present in the Menologion epigram. It says that God created the heavens, “stretched out like leather,” and painted it “with a circling dance of stars,” thereby illuminating the entire world. This active phrasing sets off a cinematic mental image where creation, fashioned from the raw materials, unfolds in the present. Basil imitates God by performing his own act of creation, stretching out the parchment and adorning it with paintings. In so doing, the epigram succinctly conjures in the mind an image of the physical, laborious, and time-consuming process of this book’s creation, from its origins as animal skin to its product as illuminated parchment.

While the epigram in the Menologion of Basil II is not technically an ekphrasis, it does contain certain ekphrastic features that move the listener to envision an image. It performs a number of re-creative acts: God as the creator of heaven and earth, Basil as the maker of the manuscript, and the anonymous poet as a painter of pictures with words. Rather than ask the question of whether or not a painted scene of God and Basil ever accompanied this epigram, we can recognize the text’s authority to operate independently of such an image. The poet is the artist, the words are the brushstrokes, the imagination is the canvas, and the hearers are made into spectators.

Notes

[1] Ruth Webb, Ekphrasis, Imagination and Persuasion in Ancient Rhetorical Theory and Practice (Farnham, 2009), quote on p. 73.

[2] Nicholas, Progymnasmata, 68.11–12, ed. Joseph Felten, Nicolai Progymnasmata (Leipzig, 1913), tr. George A. Kennedy, Progymnasmata: Greek Textbooks of Prose Composition and Rhetoric (Atlanta, 2003), 166.

[3] Liz James, and Ruth Webb, “‘To understand ultimate things and enter secret places’: ekphrasis and art in Byzantium,” Art History 14 (1991): 1–17.

[4] Nicholas Mesarites, Description of the Church of the Holy Apostles, XII.1, 4, ed. Glanville Downey, Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 47 (1957): 900, tr. Michael Angold, Nicholas Mesarites: His Life and Works (in Translation) (Liverpool, 2017), 90.

[5] Marc Lauxtermann, Byzantine Poetry from Pisides to Geometres: Texts and Contexts, vol. 1 (Vienna, 2003), 153.

[6] Ed. Andreas Rhoby, Byzantinische Epigramme in inschriftlicher Überlieferung, vol. 4 (Vienna, 2018), 455–458. Translation based on Ihor Ševčenko, “The Illuminators of the Menologium of Basil II,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 16 (1962): 245–276, esp. 272–273. The verse divisions presented here correspond to those given in the manuscript by the large incipit letters marking verses 1, 9, and 22.

[7] A facing miniature illustrating a scene described by the epigram has been hypothesized by Ševčenko, “Illuminators,” 271–273; and supported by Antonio Iacobini, “Apéndice: El cuaderno incial del ‘Menologio de Basilio II’,” in El “Menologio de Basilio II”: Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Gr. 1613: libro de estudios con ocasión de la edición facsímil, eds. Francesco D’Aiuto, and Inmaculada Pérez Martín (Vatican City and Madrid, 2008), 221–223.

[8] Aphthonios, Progymnasmata, 37, ed. Hugo Rabe, Aphthonii Progymnasmata (Leipzig, 1926), tr. Kennedy, Progymnasmata, 117. For an example, see Lynn Jones, and Henry Maguire, “A Description of the Jousts of Manuel I Komnenos,” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 26 (2002): 104–148.

[9] Jon Steffen Bruss, “Ecphrasis in fits and starts? Down to 300 BC,” in Archaic and Classical Greek Epigram, eds. Manuel Baumbach, Andrej Petrovic, and Ivana Petrovic (Cambridge, 2010), 385–403, esp. 387.

[10] Ed. Otto Veh, Prokop: Werke, vol. 5, Die Bauten (Munich: Heimeran, 1977), pp. 336–338, lines 614–625, tr. Cyril Mango, The Art of the Byzantine Empire, 312–1453 (Englewood Cliffs, N.J., 1972), 85.

Want to read more?

- Facsimile Edition: El “Menologio” de Basilio II Emperador de Bizancio: (Vat. Gr. 1613) (Madrid, 2005).

- Wolfram Hörandner, “Zur Beschreibung von Kunstwerken in der byzantinischen Dichtung – am Beispiel des Gedichts auf das Pantokratorkloster in Konstantinopel,” in Die poetische Ekphrasis von Kunstwerken: Eine literarische Tradition der Großdichtung in Antike, Mittelalter und früher Neuzeit, ed. Christine Ratkowitsch (Vienna, 2006), 203–219.

- Liz James, “Art and Lies: Text, Image and Imagination in the Medieval World,” in Icon and Word: The Power of Images in Byzantium: Studies Presented to Robin Cormack, eds. Antony Eastmond and Liz James (Aldershot, 2003), 59–72.

- Augusta Acconcia Longo, “El Poema Introductorio en Dodecasílabos Bizantinos,” in El “Menologio de Basilio II”: Città del Vaticano, Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana, Vat. Gr. 1613: libro de estudios con ocasión de la edición facsímil, eds. Francesco D’Aiuto, and Inmaculada Pérez Martín (Vatican City and Madrid, 2008), 77–89.

- Henry Maguire, “Truth and Convention in Byzantine Descriptions of Works of Art,” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 28 (1974): 113–140.

- Anneliese Paul, “Beobachtungen zu Ἐκφράσεις in Epigrammen auf Objekten: Lassen wir Epigramme sprechen!,” in Die kulturhistorische Bedeutung byzantinischer Epigramme: Akten des internationalen Workshop (Wien, 1.–2. Dezember 2006), eds. Wolfram Hörandner, and Andreas Rhoby (Vienna, 2008), 61–73.

- Ilias Taxidis, The Ekphraseis in the Byzantine Literature of the 12th Century (Alessandria, 2021).

About the author

Brad Hostetler (Ph.D. Florida State University, 2016) is Assistant Professor of Art History at Kenyon College. He specializes in the art and material culture of Late Antiquity and Byzantium, with a particular emphasis on portable luxury objects from the ninth through the twelfth centuries. He is currently writing a book that examines the nature and meaning of relics and reliquaries in Byzantium through the lens of inscriptions, including the ways in which inscribed texts mediate and guide the faithful’s engagement with, and understanding of, sacred matter.

Spread the word!

Share

Cite