All epigrams discussed in this blog post are to be found in the Database of Byzantine Book Epigrams (last consulted on 04/03/2022).

|

|

| DBBE Type 5248 Translation by De Vos, De Groot & Rouckhout (2019: 92)[1] |

Grammar played an important role in Byzantine education, as we can tell from the numerous manuscripts handing down grammatical treatises and other texts used for the teaching of grammar, such as the Homeric epics and tragedies of Euripides and Sophocles.[2] Many such manuscripts are crawling with prose scholia and glosses commenting upon the grammatical aspects of these texts, like orthography or syntax. Quite often they also contain all kinds of metrical paratexts that are (more) closely related to the texts themselves. Just like their prose counterparts, these book epigrams – varying greatly in length – can be found either in the margins of the page or directly before or after the text they are connected to.

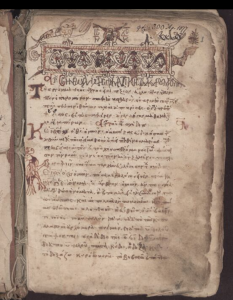

A telling example is the epigram we selected to open this blogpost with. In it, a grammatical textbook directly addresses the reader and boasts about being both concise and easily understandable. In order to find out which book is speaking to us here, we need to take a closer look at the manuscripts in which the epigram has come down to us. As it turns out, all occurrences known today appear in the close vicinity of either the Erotemata Grammaticalia (“Grammatical Questions”) or the Schedographia written by the Byzantine grammarian and philologist Manuel Moschopoulos (13th – 14th century).[3] The former ties in neatly with verse 4, which brings to mind a text written in the form of question and answer. In a 15th-century manuscript (Image 1), we can find the epigram preceding this work.

This together with over thirty more text-related book epigrams have been collected and grouped by the DBBE team under the subject “grammar”.

Introductory book epigrams

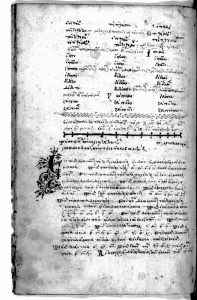

In several manuscripts, the beginning of a new text is indicated by means of a short metrical title consisting of no more than a single verse. This is also the case with both the Erotemata of Moschopoulos and the Erotemata of Manuel Chrysoloras (14th – 15th c.), another grammatical work written in question-and-answer format. In the manuscript Mon. gr. 299 (Image 2), for example, the text of Chrysoloras’ Erotemata is preceded by the following verse:

|

|

Accurate overview of grammar. |

| DBBE Occurrence 23431 Translation by the DBBE team |

In another manuscript from the 15th century, the same title is used for the Erotemata of Moschopoulos.

The following epigram introduces – in three different manuscripts – an anonymous grammatical treatise in a similar yet much more elaborate manner:

|

|

This is from me to you, my friend, in an overview, as grammar is notorious for being far-roaming. May you however be made wise – as well as I – and moreover saved, by the one and only original wisdom of God. |

| DBBE Type 3550 Translation by the DBBE team |

The epigram presents this treatise to the reader as a handy overview (ἐν συνόψει) of grammar, which in its turn is described as πολύπλανος, literally meaning “wandering in all directions”. Although we would not go as far as to consider grammar rules “devious” or even “leading astray”, they can indeed come across as going in all directions and difficult to oversee. Have we not all struggled with them? Luckily, the reader can also rely on the divine source of knowledge, which comes from God.

Book epigrams on (the value of) grammar rules

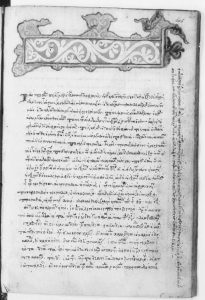

We have detected a strikingly similar imagery in a manuscript from Paris dating from the 14th or 15th century (Image 3). It features a book epigram encouraging the reader to make their way through the many rules of grammar (δίελθε τοὺς κανόνας τῆς γραμματικῆς), which again is called πολυπλανής.

|

|

If you wish to learn, my dearest friend, the definitions of the far-roaming grammar, make your way, both with pleasure and toil, through the rules concerning the masculine, feminine and neuter, through all of the verb and all declensions, and all other parts of speech as well. These will be both taught and presented clearly by this well-fed book on grammar. |

| DBBE Type 33725 Translation by the DBBE team |

The epigram is found in the right margin of an anonymous treatise concerning different aspects of grammar, including prosody and orthography. The treatise is written in question-and-answer form like the Erotemata of Moschopoulos and Chrysoloras mentioned earlier. This text too is presented as a useful and clear tool, from which the reader will benefit. The book is called “well-fed” (if we accept the conjecture πολύτροφος, formulated to remedy the πολέτοφος to be found in the manuscript), and the reader would therefore expect a voluminous treatise.[4] Ironically, the work that follows is only three pages long. We seem to be dealing with an unfinished copy, written by two different scribes. It is lacking a title and further down the text, some initials are missing.[5] The layout of the epigram itself is actually quite exceptional. It was written vertically, forcing the reader to tilt their head.

The idea that the reader will benefit from these treatises is to be found in another epigram as well, which appears twice in the vicinity of a grammatical work and also contains a didactic message. Whereas grammar in the previous epigrams was called πολύπλανος / πολυπλανής, the book is here compared to a steady, unwavering door (πύλη ἀπλανής) the reader has to pass through. Dispersive as grammar rules may come across sometimes, they do offer a hold.

Lessons from the margins …

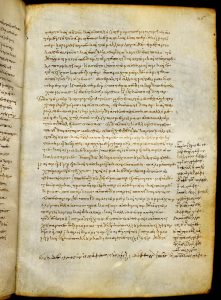

All epigrams mentioned up until now praise the value of the grammatical treatises they are connected to. The following verse scholion, however, is a lesson in grammar on its own (Image 4).

|

|

| DBBE Type 31250 Translation by Kaldellis (2015: 70)[6] |

It is one of over 50 verse scholia which the famous 12th-century poet and grammarian John Tzetzes himself added in the margins of a 9th- or 10th-century copy of Thucydides’ Histories. In this particular case, Tzetzes comments upon the spelling of ἱππῆς (from ἱππεύς “horserider”) which someone had corrected unjustly into ἱππεῖς. This is far from the only passage where Tzetzes seizes the opportunity to dive into Attic orthography, while ranting at both rival scholars and Thucydides, whom further down the same manuscript he refers to as “a puppy” once again.

… that can also make the modern reader smile

Tough as grammar rules and their many exceptions may be, they did give rise to jokes as well. A case in point is our last epigram, which is known from the Greek Anthology (AP IX.489). It alludes to the three genders in Greek, by playing with the word παιδίον (“child”), which grammatically speaking is neutre.

Γραμματικοῦ θυγάτηρ ἔτεκεν φιλότητι μιγεῖσα παιδίον ἀρσενικόν, θηλυκόν, οὐδέτερον. |

Having slept with a man the grammarian’s daughter gave birth to a child, in turn masculine, feminine & neuter. |

| DBBE Type 4453 Translation by Jay (1974: 295)[7] |

A variant of this epigram is written in the upper margin of a 14th- or 15th-century manuscript from Milan containing various grammatical works. It precedes the Disticha Catonis translated in Greek by Maximos Planoudes (c. 1255 – c. 1305). The work itself – a collection of maxims – is also accompanied by glosses and scholia. One could wonder whether this epigram is perhaps intended as a playful counterpart of these more serious notes. This last example shows that there is still a lot more to be discovered in the manuscript margins. The DBBE team gladly contributes to uncover such hidden testimonies of readership in Byzantium.

Notes

[1] I. De Vos, S. De Groot, A. Rouckhout 2019, “I am a Grammatical Textbook”. Towards a Critical Edition of a Deceivingly Simple Book Epigram, in T. Scheijnen, B. Verhelst (eds.), Parels in schrift. Huldeboek voor Marc De Groote, Ghent, 91-94.

[2] On the importance of grammar and the transmission of grammatical works, see for example:

- (for the 9th-12th c.) F. Ronconi 2012, Quelle grammaire à Byzance? La circulation des textes grammaticaux et son reflet dans les manuscrits, in G. De Gregorio (ed.), La produzione scritta tecnica e scientifica nel medioevo: Libro et documento tra scuole e professioni. Atti del Convegno internazionale di studio dell’Associazione italiana dei Paleografi e Diplomatisti Fisciano – Salerno (28-30 settembre 2009), Spoleto, 63-110.

- S. Papaioannou 2021, Theory of Literature, in S. Papaioannou (ed.), The Oxford Handbook of Byzantine Literature, New York, 75-109.

An elaborate study of some textbooks of the Palaeologan Period (13th-14th c.) can be found in F. Nousia, 2016, Byzantine Textbooks of the Palaeologan Period, Vaticano. (Further reading concerning the earlier Byzantine period can be found in the introduction of this work).

[3] For a more detailed discussion of this epigram as well as an overview of the manuscripts in which it has been preserved, see De Vos, De Groot & Rouckhout (2019: 91-94).

[4] A possible alternative could be πολυτρόφος (“nourishing”) – with an accent on the paenultimate – which would refer to the usefulness of the work and fits in the overall message of this epigram.

[5] Information on the text courtesy of Andrea Cuomo, who also noted some similarities with scholia on the grammarian Dionysios Thrax.

[6] A. Kaldellis, 2015, Byzantine Readings of Ancient Historians, Abingdon and New York.

[7] P. Jay, 1974, The Greek Anthology and Other Ancient Greek Epigrams: A Selection in Modern Verse Translations, London.

Want to read more?

- on Byzantine book epigrams and some of their characterizing features

- on notes, including book epigrams, left by John Tzetzes in another manuscript, kept in Leiden

- other metrical titles introducing grammatical works …

- … and their counterparts, single verses indicating the ending of a grammatical work

- other verse scholia

About the author

This blogpost was written by Febe Schollaert within the framework of an internship at the Database of Byzantine Book Epigrams. She holds a master’s degree in “Greek and Latin Linguistics and Literature” and is currently studying for a master’s degree in “Historical Languages and Linguistics” at Ghent University. Her research interests include narratology; textual criticism and Greek palaeography, with special interest in Byzantine poetry about grammar, in particular orthography. Her first master thesis consists of a study of the orthographical kanones by Niketas of Herakleia (11th-12th c.). She currently focuses on another Byzantine orthographical kanon (transmitted under the names of (Ptocho-)Prodromos, Mazaris or Galaction), and some issues scholars are faced with when editing such a text.

This blogpost was written by Febe Schollaert within the framework of an internship at the Database of Byzantine Book Epigrams. She holds a master’s degree in “Greek and Latin Linguistics and Literature” and is currently studying for a master’s degree in “Historical Languages and Linguistics” at Ghent University. Her research interests include narratology; textual criticism and Greek palaeography, with special interest in Byzantine poetry about grammar, in particular orthography. Her first master thesis consists of a study of the orthographical kanones by Niketas of Herakleia (11th-12th c.). She currently focuses on another Byzantine orthographical kanon (transmitted under the names of (Ptocho-)Prodromos, Mazaris or Galaction), and some issues scholars are faced with when editing such a text.

“I would like to thank the members of the DBBE team for their critical proof-reading of this blog and for sharing their insights. The translations of types 5629, 3350 and 33725 cited in this contribution are also the result of a collaboration of the DBBE team, to whom I am very grateful for their input. Special thanks goes to Ilse De Vos, Rachele Ricceri and Anne-Sophie Rouckhout, who guided me throughout the whole process of the writing of this blog and whose feedback was invaluable.”

Spread the word!

Share

Cite