Latin book epigrams can be found in numerous Western manuscripts. Just as is the case with Byzantine book epigrams, it seems that there is a lot of variation among Latin book epigrams. Some are short and formulaic, others are more refined literary compositions. Similar subgenres (scribe-, patron-, owner-, author-, reader-, text- and miniature-related) are likely to be identified both in book epigrams written in the Latin West and in the Byzantine East. Of course, a systematic collection of Latin book epigrams could allow scholars to detect generic, linguistic and cultural evolutions within the yet to be explored corpus of Latin book epigrams and compare them to their Byzantine counterparts.

In order to stimulate curiosity towards these fascinating but little-known compositions, I will discuss three examples of Latin book epigrams. The first one is a short formula, which shows that book epigrams are mostly preserved anonymously and that they are often adapted or expanded in different manuscripts. The second example is a prayer for the scribe, the author and the reader of the manuscript. It is a short, but clear example of book epigrams as poems that find their origin in the interplay between the actors in the communicative situation of manuscripts. The third case study is a more sophisticated piece of poetry, an epigram in honour of Saint Ambrose.

A Formulaic Verse

An invaluable tool to investigate the evidence of Latin book epigrams is the monumental collection of colophons by the Benedictines of Le Bouveret (Switzerland). Although this collection is presented as the anonymous collective work of the monks of the monastery of Le Bouveret, it was mostly R. P. G. Beyssac who was responsible for it. From 1965 to 1982, he published six volumes of colophons, both in prose and in verse, which he collected from Western dated manuscripts, from the oldest codices to 16th-century manuscripts. The core of this corpus consists of colophons from libraries in Paris, but Beyssac also retrieved colophons from other libraries and manuscript catalogues from all over the world. Unfortunately, but quite understandably, this series does not give a complete overview of all Latin colophons.

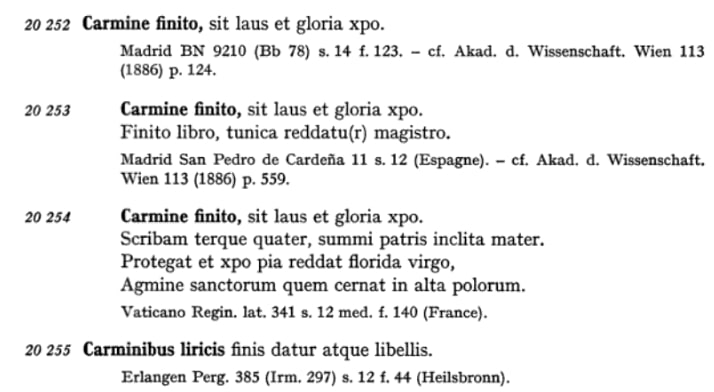

In the sixth volume, which includes colophons that do not mention any personal names, the following formulaic concluding verses appear (‘xpo’ being an abbreviation for ‘Christo’):

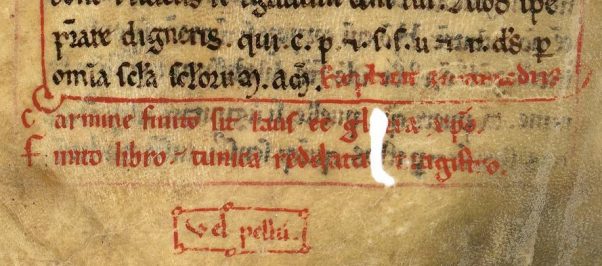

All metrical colophons of this small collection are written in Leonine verses. This metre is frequently used in medieval Latin poetry and consists of a hexameter with internal rhyme. As is typical for both Latin and Byzantine book epigrams, short formulaic epigrams are often found in expanded versions.[1] Whereas number 20 252 consists of a single verse (Now that the poem is finished, let there be praise and glory to Christ)[2], 20 253 has an extra verse (The book being finished, may the tunic be given back to the teacher).[3]

20 254 is even a bit longer (Now that the poem is finished, let there be praise and glory to Christ. May the renowned Mother of the highest Father protect the scribe three and four times and may the holy flourishing Virgin give him back to Christ. May he see Him in the heights of heavens together with the multitude of the saints). As is typical, the Virgin is asked to intercede for the scribe and to grant him a place in heaven. Note also the paradoxical “summi patris inclita mater”, pointing to Mary being the mother of Christ, who is here referred to as ‘Father’.

Three to be saved

An example of a Latin book epigram that gives an overview of different roles performed by people involved in book production is found in a manuscript preserved in Basel (Univ. A XI 65, a. 1525, f. 117) and is also recorded by the Benedictines of Le Bouveret (1982: 345):

A gehenni ignibus simul et auctorem,

Sed eternis sedibus iunge et lectorem,

Ut te laudent pariter suum creatorem.

from the fires of hell and also its author,

but let also the reader join the eternal seats,

in order that they praise You all together, their creator.

The poem is written in Goliardic verse. This is a medieval strophic meter in which a verse consists of thirteen syllables. The verses have a rhythmical, almost trochaic, pattern. Moreover, it is common in Goliardic poetry that each strophe has monorhyme, i.e. the same sound appears at the end of all verses of the same strophe (here –orem).[4] As is the case in the example above, the poet, deliberately, placed the actors who play a role in the communicative situation of book epigrams (in casu scribe, author and reader) at the end of vv. 1-3. Their importance is not only stressed by an identical metrical position but also by the rhyme. The poem culminates in God, the creator of everyone.

A comparable Byzantine example of a prayer that is expressed for the salvation of those involved in the production of manuscripts is type 2225:

τὸν ἀναγινώσκοντα μετ᾽ εὐλαβείας

φύλαττε τοὺς τρεῖς, ὦ Τριάς, τρισολβίως.

and the one who reads cautiously:

save the three of them, thrice blessed Trinity.

In these three dodecasyllables, the Trinity is implored to save yet another triad (the scribe, the owner and the reader). The parallel between the Latin and the Byzantine examples is striking and underlines again that book epigrams have similar functions in both literary cultures.

A Book Epigram on Saint Ambrose

Just as there are a lot of Byzantine book epigrams on Eastern Church Fathers, there are several laudations of Western Church Fathers in Latin book epigrams. One of the praised Fathers is Ambrose, bishop of Milan (339-397 AD). In an early printed book, Basel Univ. FJ II 1-3, p. 9, a. 1492, there is an illustrated title page of his works. Below a portrait of the writing bishop, appears a poem in elegiac couplets.

Quid tibi sancta fides, pater o memorande, rependet,

Quam tua collustrant scripta decora nimis?

Per te caesaribus vivendi norma, beate,

Praescripta est multis christicolisque bonis.

Plurima certe[5] tuis debet veneranda libellis

Religio, infractam quod facis esse fidem.

Haeretici exhorrent merito venerabile nomen.

Ambrosii, quorum malleus ipse fuit.

Nec potuere quidem verbum mutare maligni

Illius ex scriptis dogmatibusque viri.

What will holy faith, o memorable father, compensate you?

For your charming writings very much illuminate your faith.

Because of you, o blessed one, a rule of life is prescribed

to emperors and to many good Christians.

The venerable religion certainly owes a great debt to your books,

because you make sure that faith is not broken.

Heretics rightly shudder at the venerable name

of Ambrose, who himself was a hammer to them.

Malicious men were unable to change even a single word

of his writings and teachings.

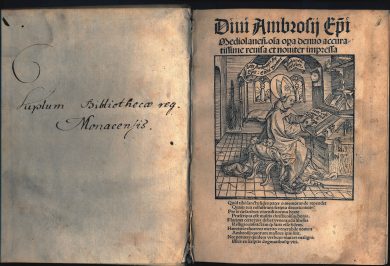

The poem was composed by Sebastian Brant (1458-1521), who was a German humanist and poet. He is mostly famous for his work Das Narrenschyff (Ship of Fools), but he also composed a series of poems on Church Fathers, such as Augustine and Ambrose, which are included in his Varia Carmina.[6] The poem quoted above is part (vv. 7-16) of a longer poem of 68 verses that appears under the heading ‘In laudem sanctissimi patris Ambrosii’ (In Honor of the Most Holy Father Ambrose).

Probably, these verses by Brant were selected for several reasons. Firstly, they express a clear praise of the spiritual value of Ambrose, a man of excellent faith who gives guidelines not only to good Christians, but also to emperors (probably a reference to his banning of emperor Theodosius from the cathedral of Milan as a punishment for the Massacre of Thessalonica in 390 AD, for which he held the emperor responsible). Also, he is portrayed as an enemy and ‘destroyer’ (‘a hammer’) of heretics. Another reason why these verses where used as a book epigram is that the last elegiac couplet is a claim of a trustworthy edition of the texts of Ambrose. Such claims are of course important when copying manuscripts.Furthermore, the popularity of Brant, as a contemporary poet, was possibly also a reason to select these verses to feature on the front page of Ambrose’s work.

Interestingly, the very same verses on Ambrose as the ones quoted above also appear on the title page of the printed volume of the works of Ambrose by Ioannes Petri de Langendorff, which was published in Basel, in 1506. The composition of both title pages is quite comparable and an influence from Basel (Univ. FJ II 1-3, a. 1492) seems possible. The fact that the same verses, although originally being part of a longer composition, are copied in other volumes is an indication of the established position of these distichs as a traditional paratext to be appended to early editions of Ambrose’s works.

A Conclusive Plea

From this very limited case study, consisting of only three examples, it is difficult to draw general conclusions on features and diffusion of Latin book epigrams. However, what the examples do indicate is that there is a lot of diversity within this genre, not only regarding length and literary quality, but also regarding meter. The example taken from Brant’s poetry furthermore indicates that book epigrams do not only appear in medieval manuscripts, but also in printed books. Moreover, it seems clear on several points that there are strong similarities between Latin and Byzantine book epigrams. Therefore, it might be a good idea to set up a database of Latin book epigrams next to or, at best, linked to the DBBE. Several Latin book epigrams with a close relation towards Byzantine ones could be linked to one another and similarities and differences between both book cultures could be studied in more detail. Not only would a database of Latin book epigrams be beneficial for the study of Latin book epigrams on their own, it might also inspire the DBBE to take a look beyond the borders of Byzantium.

Notes

[1] See, for example, the Byzantine book epigram inc. Ἡ μὲν χεὶρ ἡ γράψασα σήπεται τάφῳ, which also circulates in various several variants (DBBE Type 1974).

[2] All translations are by the author.

[3] The cultural, social or religious implications of this phrase are not immediately clear to me. Please feel free to comment below this post or to contact me should you be willing to provide more information on this practice. Besides, the note “vel pellum” below the folio does not seem to be part of the poem. Both the meter and the lay-out indicate that it is not part of the verse. See also f. 1r for similar notes. The note on f. 119v seems to be a scholion providing an alternative reading. The word ‘pellum’ is short for ‘scalpellus’, referring to a knife used by scribes. It is not immediately clear to me how it fits into the context of this folio.

[4] I would like to thank Wim Verbaal for his input as for the metrical form of this epigram.

[5] The edition of the Varia Carmina itself read ‘nostra’ instead of ‘certe’. The edition of Ioannes Petri de Langendorff, mentioned below, also reads ‘certe’.

[6] Notice that there are book epigrams on the front page and at the end of this edition as well.

Want to read more?

- Meesters, R. (forthcoming) A Plea for a Database of Latin Book Epigrams: A Case Study of Latin Book Epigrams in the Royal Library of Belgium. Proceedings of the ‘Old Books and New Technologies Conference’ 6th of May 2021. Royal Library of Belgium, Brussels.

- Reynhout, L. (2006) Formules latines de colophons. 2 vols. Bibliologia 25. Turnhout.

- For a link between Greek, Latin, Syriac and Arabic book epigrams, see McCollum, A. C. (2015) The Rejoicing Sailor and the Rotting Hand: Two Formulas in Syriac and Arabic Colophons. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies 18.1: 67-93.

- For many more laudatory Latin book epigrams in honour of the Church Fathers by Sebastian Brant, see his Varia Carmina.

About the author

Renaat Meesters is a former heuristic collaborator of the DBBE. In 2017 he completed his PhD-thesis on the edition of some Byzantine book epigrams on the Ladder of John Klimax.

“I would like to thank Rachele Ricceri for her many good suggestions for improving this text.”

Spread the word!

Share

Cite